| Berenice (оригинал) | Berenice (перевод) |

|---|---|

| MISERY is manifold. | MISERY – это многообразие. |

| The wretchedness of earth is multiform. | Убожество земли многообразно. |

| Overreaching the | Превышение |

| wide | широкий |

| horizon as the rainbow, its hues are as various as the hues of that arch, | горизонт, как радуга, его оттенки столь же разнообразны, как оттенки этой арки, |

| —as distinct too, | — тоже отлично, |

| yet as intimately blended. | но как внутренне смешанные. |

| Overreaching the wide horizon as the rainbow! | Достигнув широкого горизонта, как радуга! |

| How is it | Как это |

| that from beauty I have derived a type of unloveliness? | что из красоты я вывел тип некрасивости? |

| —from the covenant of | — из завета |

| peace a | мир а |

| simile of sorrow? | подобие печали? |

| But as, in ethics, evil is a consequence of good, so, in fact, | Но как в этике зло есть следствие добра, так и в действительности |

| out of joy is | от радости |

| sorrow born. | рождается печаль. |

| Either the memory of past bliss is the anguish of to-day, | Либо воспоминание о былом блаженстве - сегодняшняя тоска, |

| or the agonies | или агония |

| which are have their origin in the ecstasies which might have been. | которые берут свое начало в экстазах, которые могли бы быть. |

| My baptismal name is Egaeus; | Мое имя при крещении Эгей; |

| that of my family I will not mention. | что из моей семьи я не буду упоминать. |

| Yet there are no | Тем не менее, нет |

| towers in the land more time-honored than my gloomy, gray, hereditary halls. | башни в земле более освященные веками, чем мои мрачные, серые, наследственные чертоги. |

| Our line | Наша линия |

| has been called a race of visionaries; | был назван расой провидцев; |

| and in many striking particulars —in the | и во многих поразительных подробностях — в |

| character | персонаж |

| of the family mansion —in the frescos of the chief saloon —in the tapestries of | семейного особняка — на фресках главного салона — на гобеленах |

| the | в |

| dormitories —in the chiselling of some buttresses in the armory —but more | общежития — в точении некоторых контрфорсов в оружейной — но более |

| especially | особенно |

| in the gallery of antique paintings —in the fashion of the library chamber —and, | в галерее старинных картин — по образцу библиотечной палаты — и, |

| lastly, | наконец, |

| in the very peculiar nature of the library’s contents, there is more than | в очень своеобразном характере содержимого библиотеки есть более чем |

| sufficient | достаточный |

| evidence to warrant the belief. | доказательства, подтверждающие веру. |

| The recollections of my earliest years are connected with that chamber, | Воспоминания моих ранних лет связаны с той палатой, |

| and with its | и с его |

| volumes —of which latter I will say no more. | тома, о последнем я больше ничего не скажу. |

| Here died my mother. | Здесь умерла моя мать. |

| Herein was I born. | Здесь я родился. |

| But it is mere idleness to say that I had not lived before | Но праздность говорить, что я не жил раньше |

| —that the | - что |

| soul has no previous existence. | душа не имеет предыдущего существования. |

| You deny it? | Вы это отрицаете? |

| —let us not argue the matter. | — не будем спорить. |

| Convinced myself, I seek not to convince. | Убедил себя, я стараюсь не убеждать. |

| There is, however, a remembrance of | Однако есть воспоминание о |

| aerial | антенна |

| forms —of spiritual and meaning eyes —of sounds, musical yet sad —a remembrance | формы — духовных и смысловых глаз — звуков, музыкальных, но грустных — воспоминание |

| which will not be excluded; | которые не будут исключены; |

| a memory like a shadow, vague, variable, indefinite, | память, подобная тени, смутная, изменчивая, неопределенная, |

| unsteady; | неустойчивый; |

| and like a shadow, too, in the impossibility of my getting rid of it | и как тень, в невозможности избавиться от нее |

| while the | в то время как |

| sunlight of my reason shall exist. | солнечный свет моего разума будет существовать. |

| In that chamber was I born. | В этой комнате родился я. |

| Thus awaking from the long night of what seemed, | Таким образом, проснувшись от долгой ночи того, что казалось, |

| but was | но был |

| not, nonentity, at once into the very regions of fairy-land —into a palace of | нет, ничтожество, сразу в самые края сказочной страны — во дворец |

| imagination | воображение |

| —into the wild dominions of monastic thought and erudition —it is not singular | — в дикие владения монашеской мысли и эрудиции — это не единичный |

| that I | что я |

| gazed around me with a startled and ardent eye —that I loitered away my boyhood | смотрел вокруг меня испуганным и пылким взглядом, что я слонялся без дела моего отрочества |

| in | в |

| books, and dissipated my youth in reverie; | книги и рассеял свою юность в мечтах ; |

| but it is singular that as years | но необычно то, что годы |

| rolled away, | откатился, |

| and the noon of manhood found me still in the mansion of my fathers —it is | и полдень зрелости застал меня еще в особняке моих отцов — это |

| wonderful | замечательно |

| what stagnation there fell upon the springs of my life —wonderful how total an | какой застой обрушился на источники моей жизни - удивительно, как тотально |

| inversion took place in the character of my commonest thought. | инверсия произошла в характере моей самой обыденной мысли. |

| The realities of | Реалии |

| the | в |

| world affected me as visions, and as visions only, while the wild ideas of the | мир подействовал на меня как видения, и только как видения, в то время как дикие идеи |

| land of | земля |

| dreams became, in turn, —not the material of my every-day existence-but in very | сны стали, в свою очередь, — не материалом моего повседневного существования, а в очень |

| deed | поступок |

| that existence utterly and solely in itself. | это существование полностью и исключительно в себе. |

| - | - |

| Berenice and I were cousins, and we grew up together in my paternal halls. | Мы с Беренис были двоюродными сестрами и росли вместе в моих отцовских чертогах. |

| Yet differently we grew —I ill of health, and buried in gloom —she agile, | Но по-разному мы росли — я больна и погружена в мрак — она проворна, |

| graceful, and | изящный, и |

| overflowing with energy; | переполненный энергией; |

| hers the ramble on the hill-side —mine the studies of | ее прогулка по склону холма - мои исследования |

| the | в |

| cloister —I living within my own heart, and addicted body and soul to the most | монастырь — я живу в собственном сердце и предаю душу и тело самому |

| intense | интенсивный |

| and painful meditation —she roaming carelessly through life with no thought of | и мучительные размышления — она беззаботно бродит по жизни, не думая о |

| the | в |

| shadows in her path, or the silent flight of the ravenwinged hours. | тени на ее пути, или безмолвный полет воронокрылых часов. |

| Berenice! | Беренис! |

| —I call | -Я звоню |

| upon her name —Berenice! | по ее имени — Береника! |

| —and from the gray ruins of memory a thousand | — и из серых руин памяти тысяча |

| tumultuous recollections are startled at the sound! | бурные воспоминания вздрагивают от звука! |

| Ah! | Ах! |

| vividly is her image | яркий ее образ |

| before me | передо мной |

| now, as in the early days of her lightheartedness and joy! | теперь, как в первые дни ее беззаботности и радости! |

| Oh! | Ой! |

| gorgeous yet | великолепный еще |

| fantastic | фантастика |

| beauty! | красота! |

| Oh! | Ой! |

| sylph amid the shrubberies of Arnheim! | сильфида среди кустов Арнхейма! |

| —Oh! | -Ой! |

| Naiad among its | Наяда среди своих |

| fountains! | фонтаны! |

| —and then —then all is mystery and terror, and a tale which should not be told. | — а потом — все тайна и ужас, и сказка, которую не следует рассказывать. |

| Disease —a fatal disease —fell like the simoom upon her frame, and, even while I | Болезнь — смертельная болезнь — обрушилась на ее тело, как самум, и, даже когда я |

| gazed upon her, the spirit of change swept, over her, pervading her mind, | смотрел на нее, дух перемен проносился над ней, проникая в ее разум, |

| her habits, | ее привычки, |

| and her character, and, in a manner the most subtle and terrible, | и ее характер, и, в своем роде, самый хитрый и ужасный, |

| disturbing even the | беспокоит даже |

| identity of her person! | личность ее человека! |

| Alas! | Увы! |

| the destroyer came and went, and the victim | разрушитель пришел и ушел, а жертва |

| —where was | -где был |

| she, I knew her not —or knew her no longer as Berenice. | она, я не знал ее - или не знал ее больше как Беренику. |

| Among the numerous train of maladies superinduced by that fatal and primary one | Среди многочисленных болезней, вызванных этим роковым и первичным |

| which effected a revolution of so horrible a kind in the moral and physical | которая произвела столь ужасную революцию в моральном и физическом |

| being of my | быть моим |

| cousin, may be mentioned as the most distressing and obstinate in its nature, | двоюродный брат, можно назвать самым беспокойным и упрямым по своей природе, |

| a species | вид |

| of epilepsy not unfrequently terminating in trance itself —trance very nearly | эпилепсии, нередко заканчивающейся самим трансом — трансом почти |

| resembling positive dissolution, and from which her manner of recovery was in | напоминающий положительное растворение, и от которого ее способ восстановления был в |

| most | самый |

| instances, startlingly abrupt. | случаи, поразительно резкие. |

| In the mean time my own disease —for I have been | Тем временем моя собственная болезнь — ибо я |

| told | сказал |

| that I should call it by no other appelation —my own disease, then, | что я не должен называть это никаким другим названием — моя собственная болезнь, значит, |

| grew rapidly upon | быстро вырос на |

| me, and assumed finally a monomaniac character of a novel and extraordinary | меня, и принял, наконец, мономаниакальный характер нового и экстраординарного |

| form — | форма - |

| hourly and momently gaining vigor —and at length obtaining over me the most | ежечасно и мгновенно набирая силу — и в конце концов овладев мной |

| incomprehensible ascendancy. | непонятное господство. |

| This monomania, if I must so term it, consisted in a morbid irritability of | Эта мономания, если можно так выразиться, состояла в болезненной раздражительности |

| those | те |

| properties of the mind in metaphysical science termed the attentive. | свойства ума в метафизической науке называются внимательными. |

| It is more than | Это больше, чем |

| probable that I am not understood; | вероятно, меня не понимают; |

| but I fear, indeed, that it is in no manner | но я действительно боюсь, что это никоим образом |

| possible to | возможно |

| convey to the mind of the merely general reader, an adequate idea of that | донести до ума обычного читателя адекватное представление о том, что |

| nervous | нервный |

| intensity of interest with which, in my case, the powers of meditation (not to | интенсивности интереса, с которым в моем случае сила медитации (не |

| speak | говорить |

| technically) busied and buried themselves, in the contemplation of even the most | технически) занимались и уткнулись в созерцание даже самых |

| ordinary objects of the universe. | обычные объекты вселенной. |

| To muse for long unwearied hours with my attention riveted to some frivolous | Чтобы размышлять в течение долгих неутомимых часов с моим вниманием, прикованным к какой-то легкомысленной |

| device | устройство |

| on the margin, or in the topography of a book; | на полях или в топографии книги; |

| to become absorbed for the | быть поглощенным для |

| better part of | лучшая часть |

| a summer’s day, in a quaint shadow falling aslant upon the tapestry, | летний день, в причудливой тени, падающей наискось на гобелен, |

| or upon the door; | или на двери; |

| to lose myself for an entire night in watching the steady flame of a lamp, | потеряться на всю ночь, наблюдая за ровным пламенем лампы, |

| or the embers | или угли |

| of a fire; | пожара; |

| to dream away whole days over the perfume of a flower; | мечтать целыми днями над ароматом цветка; |

| to repeat | повторять |

| monotonously some common word, until the sound, by dint of frequent repetition, | монотонно какое-то обычное слово, пока звук, благодаря частому повторению, не |

| ceased to convey any idea whatever to the mind; | перестал передавать в разум какую-либо идею; |

| to lose all sense of motion or | потерять всякое чувство движения или |

| physical | физический |

| existence, by means of absolute bodily quiescence long and obstinately | существование, посредством абсолютного телесного покоя, долго и упрямо |

| persevered in; | упорствовал в; |

| —such were a few of the most common and least pernicious vagaries induced by a | — таковы были некоторые из наиболее распространенных и наименее пагубных капризов, вызванных |

| condition of the mental faculties, not, indeed, altogether unparalleled, | состояние умственных способностей, не совсем беспрецедентное, |

| but certainly | но конечно |

| bidding defiance to anything like analysis or explanation. | бросая вызов чему-либо, например анализу или объяснению. |

| Yet let me not be misapprehended. | И все же позвольте мне не ошибиться. |

| —The undue, earnest, and morbid attention thus | — Неуместное, серьезное и болезненное внимание, таким образом, |

| excited by objects in their own nature frivolous, must not be confounded in | возбуждаемые предметами по своей природе легкомысленными, не следует смешивать |

| character | персонаж |

| with that ruminating propensity common to all mankind, and more especially | с той склонностью к размышлениям, общей для всего человечества, и особенно |

| indulged | баловался |

| in by persons of ardent imagination. | в людей с пылким воображением. |

| It was not even, as might be at first | Это было даже не так, как могло бы быть сначала |

| supposed, an | предполагается, |

| extreme condition or exaggeration of such propensity, but primarily and | крайнее состояние или преувеличение такой склонности, но в первую очередь и |

| essentially | по сути |

| distinct and different. | отчетливые и разные. |

| In the one instance, the dreamer, or enthusiast, | В одном случае мечтатель или энтузиаст, |

| being interested | быть заинтересованным |

| by an object usually not frivolous, imperceptibly loses sight of this object in | предметом обычно не легкомысленным, незаметно упускает этот предмет из виду в |

| wilderness of deductions and suggestions issuing therefrom, until, | пустыня выводов и предположений, вытекающих из них, пока, |

| at the conclusion of | по завершении |

| a day dream often replete with luxury, he finds the incitamentum or first cause | сон наяву, часто изобилующий роскошью, он находит incitamentum или первопричину |

| of his | его |

| musings entirely vanished and forgotten. | размышления полностью исчезли и забылись. |

| In my case the primary object was | В моем случае основным объектом был |

| invariably | неизменно |

| frivolous, although assuming, through the medium of my distempered vision, a | легкомысленно, хотя и предполагая, благодаря моему смутному видению, |

| refracted and unreal importance. | преломленное и нереальное значение. |

| Few deductions, if any, were made; | Было сделано несколько выводов, если таковые вообще были; |

| and those few | и те немногие |

| pertinaciously returning in upon the original object as a centre. | настойчиво возвращаясь к исходному объекту как к центру. |

| The meditations were | Медитации были |

| never pleasurable; | никогда не доставляет удовольствия; |

| and, at the termination of the reverie, the first cause, | и, по окончании задумчивости, первая причина, |

| so far from | так далеко от |

| being out of sight, had attained that supernaturally exaggerated interest which | находясь вне поля зрения, приобрел тот сверхъестественно преувеличенный интерес, который |

| was the | был |

| prevailing feature of the disease. | преобладающий признак заболевания. |

| In a word, the powers of mind more | Словом, силы ума более |

| particularly | особенно |

| exercised were, with me, as I have said before, the attentive, and are, | опытные были со мной, как я уже говорил, внимательные, и есть, |

| with the daydreamer, | с мечтателем, |

| the speculative. | спекулятивный. |

| My books, at this epoch, if they did not actually serve to irritate the | Мои книги в ту эпоху, если они и не раздражали |

| disorder, partook, it | расстройство, участие, это |

| will be perceived, largely, in their imaginative and inconsequential nature, | будут восприниматься в основном из-за их воображаемой и несущественной природы, |

| of the | принадлежащий |

| characteristic qualities of the disorder itself. | характерные качества самого расстройства. |

| I well remember, among others, | Я хорошо помню, среди прочего, |

| the treatise | трактат |

| of the noble Italian Coelius Secundus Curio «de Amplitudine Beati Regni dei»; | знатного итальянца Целия Секундуса Куриона «de Amplitudine Beati Regni dei»; |

| St. | св. |

| Austin’s great work, the «City of God»; | великая работа Остина «Город Бога»; |

| and Tertullian «de Carne Christi,» | и Тертуллиан «de Carne Christi», |

| in which the | в которой |

| paradoxical sentence «Mortuus est Dei filius; | парадоксальное предложение «Mortuus est Dei filius; |

| credible est quia ineptum est: | заслуживающий доверия est quia ineptum est: |

| et sepultus | и сепультус |

| resurrexit; | возрождение; |

| certum est quia impossibile est» occupied my undivided time, | certum est quia impossibile est» занимало мое безраздельное время, |

| for many | для многих |

| weeks of laborious and fruitless investigation. | недели кропотливого и бесплодного расследования. |

| Thus it will appear that, shaken from its balance only by trivial things, | Таким образом, будет казаться, что, выведенный из равновесия лишь тривиальными вещами, |

| my reason bore | моя причина скучна |

| resemblance to that ocean-crag spoken of by Ptolemy Hephestion, which steadily | сходство с той океанской скалой, о которой говорил Птолемей Гефестион, которая неуклонно |

| resisting the attacks of human violence, and the fiercer fury of the waters and | сопротивляясь нападениям человеческого насилия и яростной ярости вод и |

| the | в |

| winds, trembled only to the touch of the flower called Asphodel. | ветры, дрожали только от прикосновения цветка по имени Асфодель. |

| And although, to a careless thinker, it might appear a matter beyond doubt, | И хотя небрежному мыслителю это может показаться несомненным, |

| that the | что |

| alteration produced by her unhappy malady, in the moral condition of Berenice, | изменение, вызванное ее несчастным недугом, в моральном состоянии Береники, |

| would | бы |

| afford me many objects for the exercise of that intense and abnormal meditation | предоставьте мне много объектов для осуществления этой интенсивной и ненормальной медитации |

| whose | чья |

| nature I have been at some trouble in explaining, yet such was not in any | природы, которую я с трудом объяснял, однако ни в одном |

| degree the | степень |

| case. | кейс. |

| In the lucid intervals of my infirmity, her calamity, indeed, | В ясные промежутки моей немощи, ее бедствия, воистину, |

| gave me pain, and, | причинил мне боль, и, |

| taking deeply to heart that total wreck of her fair and gentle life, | глубоко принимая к сердцу полное крушение ее прекрасной и нежной жизни, |

| I did not fall to ponder | я не стал задумываться |

| frequently and bitterly upon the wonderworking means by which so strange a | часто и горько отзывались о чудотворных средствах, с помощью которых столь странный |

| revolution had been so suddenly brought to pass. | революция произошла так внезапно. |

| But these reflections partook | Но эти размышления участвовали |

| not of | не из |

| the idiosyncrasy of my disease, and were such as would have occurred, | идиосинкразия моей болезни, и если бы это произошло, |

| under similar | под аналогичным |

| circumstances, to the ordinary mass of mankind. | обстоятельствах, к обычной массе человечества. |

| True to its own character, | Верный своему характеру, |

| my disorder | мое расстройство |

| revelled in the less important but more startling changes wrought in the | наслаждался менее важными, но более поразительными изменениями, произошедшими в |

| physical frame | физическая структура |

| of Berenice —in the singular and most appalling distortion of her personal | Береники — в единственном и ужасном искажении ее личной |

| identity. | личность. |

| During the brightest days of her unparalleled beauty, most surely I had never | В самые яркие дни ее несравненной красоты я, конечно же, никогда не |

| loved | любил |

| her. | ей. |

| In the strange anomaly of my existence, feelings with me, had never been | В странной аномалии моего существования чувства ко мне никогда не были |

| of the | принадлежащий |

| heart, and my passions always were of the mind. | сердцем, а страсти мои всегда были от ума. |

| Through the gray of the early | Сквозь серость раннего |

| morning —among the trellissed shadows of the forest at noonday —and in the | утром — среди решетчатых теней леса в полдень — и в |

| silence | тишина |

| of my library at night, she had flitted by my eyes, and I had seen her —not as | моей библиотеки ночью, она промелькнула перед моими глазами, и я увидел ее — не так, как |

| the living | живой |

| and breathing Berenice, but as the Berenice of a dream —not as a being of the | и дышащая Береника, но как Береника сна, а не как существо |

| earth, | земной шар, |

| earthy, but as the abstraction of such a being-not as a thing to admire, | земное, но как абстракция такого существа, а не как предмет для восхищения, |

| but to analyze — | но анализировать — |

| not as an object of love, but as the theme of the most abstruse although | не как предмет любви, а как тема самого заумного, хотя и |

| desultory | бессвязный |

| speculation. | спекуляция. |

| And now —now I shuddered in her presence, and grew pale at her | И теперь — теперь я содрогался в ее присутствии и бледнел при ней |

| approach; | подход; |

| yet bitterly lamenting her fallen and desolate condition, | но горько оплакивая свое падшее и опустошенное состояние, |

| I called to mind that | Я вспомнил, что |

| she had loved me long, and, in an evil moment, I spoke to her of marriage. | она любила меня давно, и в злой момент я заговорил с ней о браке. |

| And at length the period of our nuptials was approaching, when, upon an | И, наконец, приближался период нашей свадьбы, когда, |

| afternoon in | полдень в |

| the winter of the year, —one of those unseasonably warm, calm, and misty days | зима года, — один из тех не по сезону теплых, тихих и туманных дней |

| which | который |

| are the nurse of the beautiful Halcyon1, —I sat, (and sat, as I thought, alone, | кормилица прекрасного Алкиона1, — я сидел, (и сидел, как мне казалось, один, |

| ) in the | ) в |

| inner apartment of the library. | внутренняя квартира библиотеки. |

| But uplifting my eyes I saw that Berenice stood | Но подняв глаза, я увидел, что Береника стоит |

| before | до |

| me. | мне. |

| - | - |

| Was it my own excited imagination —or the misty influence of the atmosphere —or | Было ли это моим возбужденным воображением — или туманным влиянием атмосферы — или |

| the | в |

| uncertain twilight of the chamber —or the gray draperies which fell around her | неуверенные сумерки комнаты — или серые драпировки, которые упали вокруг нее |

| figure | фигура |

| —that caused in it so vacillating and indistinct an outline? | — что вызвало в нем такой зыбкий и неясный абрис? |

| I could not tell. | Я не мог сказать. |

| She spoke no | Она говорила нет |

| word, I —not for worlds could I have uttered a syllable. | слово, я — ни за что на свете не мог бы я произнести ни слога. |

| An icy chill ran | Ледяной холод пробежал |

| through my | через мой |

| frame; | Рамка; |

| a sense of insufferable anxiety oppressed me; | чувство невыносимой тревоги угнетало меня; |

| a consuming curiosity | всепоглощающее любопытство |

| pervaded | пронизан |

| my soul; | моя душа; |

| and sinking back upon the chair, I remained for some time breathless | и, откинувшись на спинку стула, некоторое время я задыхался |

| and | а также |

| motionless, with my eyes riveted upon her person. | неподвижно, с моим взглядом, прикованным к ее лицу. |

| Alas! | Увы! |

| its emaciation was | его истощение было |

| excessive, | излишний, |

| and not one vestige of the former being, lurked in any single line of the | и ни один след прежнего не скрывался ни в одной строчке |

| contour. | контур. |

| My | Мой |

| burning glances at length fell upon the face. | горящие взгляды наконец упали на лицо. |

| The forehead was high, and very pale, and singularly placid; | Лоб был высокий, очень бледный и необыкновенно безмятежный; |

| and the once jetty | и некогда пристань |

| hair fell | волосы упали |

| partially over it, and overshadowed the hollow temples with innumerable | частично над ним и затмевали впалые виски бесчисленными |

| ringlets now | локоны сейчас |

| of a vivid yellow, and Jarring discordantly, in their fantastic character, | ярко-желтого цвета и диссонансно, по своему фантастическому характеру, |

| with the | с |

| reigning melancholy of the countenance. | царящая меланхолия на лице. |

| The eyes were lifeless, and lustreless, | Глаза были безжизненными и безжизненными, |

| and | а также |

| seemingly pupil-less, and I shrank involuntarily from their glassy stare to the | казалось бы, без зрачков, и я невольно сжался от их остекленевших взглядов к |

| contemplation of the thin and shrunken lips. | созерцание тонких и сморщенных губ. |

| They parted; | Они расстались; |

| and in a smile of | и в улыбке |

| peculiar | своеобразный |

| meaning, the teeth of the changed Berenice disclosed themselves slowly to my | то есть зубы изменившейся Береники медленно открывались моему |

| view. | Посмотреть. |

| Would to God that I had never beheld them, or that, having done so, I had died! | О, если бы я никогда не видел их или, увидев это, я умер! |

| 1 For as Jove, during the winter season, gives twice seven days of warmth, | 1 Ибо, как Юпитер в зимнее время дает дважды по семь дней тепла, |

| men have | мужчины имеют |

| called this clement and temperate time the nurse of the beautiful Halcyon | назвал это мягкое и умеренное время кормилицей прекрасного Алкиона |

| —Simonides. | — Симонидес. |

| The shutting of a door disturbed me, and, looking up, I found that my cousin had | Меня потревожило закрытие двери, и, подняв глаза, я обнаружил, что мой кузен |

| departed from the chamber. | вышел из палаты. |

| But from the disordered chamber of my brain, had not, | Но из беспорядочной камеры моего мозга не было, |

| alas! | увы! |

| departed, and would not be driven away, the white and ghastly spectrum of | ушел, и его не прогонят, белый и призрачный спектр |

| the | в |

| teeth. | зубы. |

| Not a speck on their surface —not a shade on their enamel —not an | Ни пятнышка на их поверхности, ни тени на эмали, ни |

| indenture in | договор в |

| their edges —but what that period of her smile had sufficed to brand in upon my | их края, но что этого периода ее улыбки было достаточно, чтобы оставить клеймо на моем |

| memory. | Память. |

| I saw them now even more unequivocally than I beheld them then. | Теперь я видел их еще более отчетливо, чем тогда. |

| The teeth! | Зубы! |

| —the teeth! | -зубы! |

| —they were here, and there, and everywhere, and visibly and palpably | — они были и там, и там, и повсюду, и зримо и осязаемо |

| before me; | передо мной; |

| long, narrow, and excessively white, with the pale lips writhing | длинные, узкие и чрезмерно белые, с бледными губами, извивающимися |

| about them, | о них, |

| as in the very moment of their first terrible development. | как в самый момент их первого ужасного развития. |

| Then came the full | Потом наступил полный |

| fury of my | ярость моя |

| monomania, and I struggled in vain against its strange and irresistible | мономания, и я тщетно боролся с ее странным и непреодолимым |

| influence. | влияние. |

| In the | В |

| multiplied objects of the external world I had no thoughts but for the teeth. | множество предметов внешнего мира, кроме зубов, у меня не было мыслей. |

| For these I | Для этих я |

| longed with a phrenzied desire. | томился бешеным желанием. |

| All other matters and all different interests | Все остальные дела и все разные интересы |

| became | стал |

| absorbed in their single contemplation. | поглощены своим единым созерцанием. |

| They —they alone were present to the | Они — только они присутствовали на |

| mental | психический |

| eye, and they, in their sole individuality, became the essence of my mental | глаза, и они в своей единственной индивидуальности стали сущностью моего ментального |

| life. | жизнь. |

| I held | Я держал |

| them in every light. | их в каждом свете. |

| I turned them in every attitude. | Я изменил их во всех отношениях. |

| I surveyed their | я опросил их |

| characteristics. | характеристики. |

| I | я |

| dwelt upon their peculiarities. | остановился на их особенностях. |

| I pondered upon their conformation. | Я задумался над их телосложением. |

| I mused upon the | я размышлял о |

| alteration in their nature. | изменение их характера. |

| I shuddered as I assigned to them in imagination a | Я содрогнулся, приписав им в воображении |

| sensitive | чувствительный |

| and sentient power, and even when unassisted by the lips, a capability of moral | и чувственная сила, и даже без помощи губ, способность морального |

| expression. | выражение. |

| Of Mad’selle Salle it has been well said, «que tous ses pas etaient | О Mad’selle Salle хорошо сказано: «que tous ses pas etaient |

| des | де |

| sentiments,» and of Berenice I more seriously believed que toutes ses dents | чувствах», а Беренис я более серьезно верил в que toutes ses dents |

| etaient des | etaient des |

| idees. | идеи. |

| Des idees! | С идеями! |

| —ah here was the idiotic thought that destroyed me! | — ах, вот идиотская мысль меня погубила! |

| Des idees! | С идеями! |

| —ah | -ах |

| therefore it was that I coveted them so madly! | поэтому я так безумно желал их! |

| I felt that their possession | Я чувствовал, что их владение |

| could alone | мог один |

| ever restore me to peace, in giving me back to reason. | когда-нибудь вернешь мне покой, вернув мне разум. |

| And the evening closed in upon me thus-and then the darkness came, and tarried, | И вот так сомкнулся надо мной вечер, а потом наступила тьма и остановилась, |

| and | а также |

| went —and the day again dawned —and the mists of a second night were now | пошел — и снова рассветал день — и туманы второй ночи были теперь |

| gathering around —and still I sat motionless in that solitary room; | собирался вокруг — и все же я сидел неподвижно в этой одинокой комнате; |

| and still I sat buried | и все же я сидел похороненный |

| in meditation, and still the phantasma of the teeth maintained its terrible | в медитации, и фантазия о зубах все еще сохраняла свое ужасное |

| ascendancy | господство |

| as, with the most vivid hideous distinctness, it floated about amid the | как с самой яркой отвратительной отчетливостью он плавал среди |

| changing lights | изменение света |

| and shadows of the chamber. | и тени камеры. |

| At length there broke in upon my dreams a cry as of | Наконец мои сны прервал крик, |

| horror and dismay; | ужас и смятение; |

| and thereunto, after a pause, succeeded the sound of troubled | а затем, после паузы, последовал звук беспокойного |

| voices, intermingled with many low moanings of sorrow, or of pain. | голоса, смешанные со множеством тихих стонов печали или боли. |

| I arose from my | я возник из своего |

| seat and, throwing open one of the doors of the library, saw standing out in the | сиденье и, распахнув одну из дверей библиотеки, увидел стоящую в |

| antechamber a servant maiden, all in tears, who told me that Berenice was —no | служанка, вся в слезах, которая сказала мне, что Береника была - нет |

| more. | более. |

| She had been seized with epilepsy in the early morning, and now, | Рано утром у нее случилась эпилепсия, и теперь, |

| at the closing in of | при закрытии |

| the night, the grave was ready for its tenant, and all the preparations for the | ночь, могила была готова для ее обитателя, и все приготовления к |

| burial | захоронение |

| were completed. | были завершены. |

| I found myself sitting in the library, and again sitting there | Я обнаружил, что сижу в библиотеке, и снова сижу там |

| alone. | один. |

| It | Это |

| seemed that I had newly awakened from a confused and exciting dream. | казалось, что я только что проснулся от спутанного и волнующего сна. |

| I knew that it | я знал, что это |

| was now midnight, and I was well aware that since the setting of the sun | была уже полночь, и я прекрасно понимал, что с момента захода солнца |

| Berenice had | Беренис была |

| been interred. | был предан земле. |

| But of that dreary period which intervened I had no positive —at | Но от того унылого периода, который наступил, у меня не было положительного — в |

| least | наименее |

| no definite comprehension. | нет определенного понимания. |

| Yet its memory was replete with horror —horror more | И все же его память была полна ужаса — ужаса еще больше. |

| horrible from being vague, and terror more terrible from ambiguity. | ужасно от неопределенности, и ужас еще страшнее от двусмысленности. |

| It was a fearful | Это было страшно |

| page in the record my existence, written all over with dim, and hideous, and | страница в записи о моем существовании, сплошь исписанная тусклыми, отвратительными и |

| unintelligible recollections. | непонятные воспоминания. |

| I strived to decypher them, but in vain; | Я пытался расшифровать их, но тщетно; |

| while ever and | в то время как когда-либо и |

| anon, like the spirit of a departed sound, the shrill and piercing shriek of a | скоро, словно дух ушедшего звука, пронзительный и пронзительный крик |

| female voice | женский голос |

| seemed to be ringing in my ears. | казалось, звенит у меня в ушах. |

| I had done a deed —what was it? | Я совершил поступок — что это было? |

| I asked myself the | Я спросил себя |

| question aloud, and the whispering echoes of the chamber answered me, «what was | вопрос вслух, и шепчущее эхо комнаты ответило мне: «что было |

| it?» | Это?" |

| On the table beside me burned a lamp, and near it lay a little box. | На столе рядом со мной горела лампа, а возле нее лежала коробочка. |

| It was of no | Это было не так |

| remarkable character, and I had seen it frequently before, for it was the | замечательный характер, и я часто видел его раньше, потому что это был |

| property of the | собственность |

| family physician; | семейный врач; |

| but how came it there, upon my table, and why did I shudder in | но как оно попало туда, на мой стол, и почему я содрогнулся в |

| regarding it? | относительно этого? |

| These things were in no manner to be accounted for, and my eyes at | Эти вещи ни в коей мере не поддавались объяснению, и мои глаза на |

| length dropped to the open pages of a book, and to a sentence underscored | длина перешла к открытым страницам книги и к подчеркнутому предложению |

| therein. | в нем. |

| The | |

| words were the singular but simple ones of the poet Ebn Zaiat, «Dicebant mihi sodales | слова были единственными, но простыми словами поэта Эбн Зайата, «Dicebant mihi sodales |

| si sepulchrum amicae visitarem, curas meas aliquantulum fore levatas. | si sepulchrum amicae visitarem, curas meas aliquantulum fore levatas. |

| «Why then, as I | «Почему же тогда, как я |

| perused them, did the hairs of my head erect themselves on end, and the blood | просматривал их, вставали ли дыбом волосы на голове моей, и кровь |

| of my | моего |

| body become congealed within my veins? | тело застыло в моих венах? |

| There came a light tap at the library | В библиотеке раздался легкий стук |

| door, | дверь, |

| and pale as the tenant of a tomb, a menial entered upon tiptoe. | и бледный, как хранитель могилы, слуга вошел на цыпочках. |

| His looks were | Его внешность была |

| wild | дикий |

| with terror, and he spoke to me in a voice tremulous, husky, and very low. | с ужасом, и он говорил со мной голосом дрожащим, хриплым и очень низким. |

| What said | Что сказал |

| he? | он? |

| —some broken sentences I heard. | — несколько сломанных предложений, которые я слышал. |

| He told of a wild cry disturbing the | Он рассказал о диком крике, нарушившем |

| silence of the | тишина |

| night —of the gathering together of the household-of a search in the direction | ночь — сбора домочадцев — обыска в направлении |

| of the | принадлежащий |

| sound; | звук; |

| —and then his tones grew thrillingly distinct as he whispered me of a | — а затем его тон стал волнующе отчетливым, когда он прошептал мне |

| violated | нарушен |

| grave —of a disfigured body enshrouded, yet still breathing, still palpitating, | могила — изуродованного тела, закутанного в саван, но все еще дышащего, все еще трепещущего, |

| still alive! | еще жив! |

| He pointed to garments;-they were muddy and clotted with gore. | Он указал на одежду: она была грязной и запачканной кровью. |

| I spoke not, | Я не говорил, |

| and he | и он |

| took me gently by the hand; | нежно взял меня за руку; |

| —it was indented with the impress of human nails. | — на нем был отпечаток человеческих ногтей. |

| He | Он |

| directed my attention to some object against the wall; | направил свое внимание на какой-то предмет у стены; |

| —I looked at it for some | — Я смотрел на это для некоторых |

| minutes; | минуты; |

| —it was a spade. | — это была лопата. |

| With a shriek I bounded to the table, and grasped the box that | С воплем я подскочил к столу и схватил коробку, |

| lay | класть |

| upon it. | на него. |

| But I could not force it open; | Но я не мог заставить его открыться; |

| and in my tremor it slipped from my | и в моем трепете он выскользнул из моего |

| hands, and | руки и |

| fell heavily, and burst into pieces; | тяжело упал и разлетелся на куски; |

| and from it, with a rattling sound, | и оттуда, с грохотом, |

| there rolled out | там выкатился |

| some instruments of dental surgery, intermingled with thirty-two small, | некоторые инструменты стоматологической хирургии, смешанные с тридцатью двумя маленькими, |

| white and | белый и |

| ivory-looking substances that were scattered to and fro about the floor. | вещества, похожие на слоновую кость, которые были разбросаны по полу взад и вперед. |

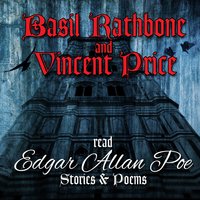

Перевод текста песни Berenice - Vincent Price, Basil Rathbone

Информация о песне На данной странице вы можете ознакомиться с текстом песни Berenice , исполнителя -Vincent Price

В жанре:Саундтреки

Дата выпуска:14.08.2013

Выберите на какой язык перевести:

Напишите что вы думаете о тексте песни!

Другие песни исполнителя:

| Название | Год |

|---|---|

| 2013 | |

| 2013 | |

| 2013 | |

| 2013 |